- The Stonehenge Altar Stone may have come from the Midlands or even Scotland

- New geological analysis suggests its geology doesn’t match most Welsh

- The Stonehenge Altar Stone was probably not sourced from the Old Red Sandstone of the Anglo-Welsh Basin: Time to broaden our geographic and stratigraphic horizons?

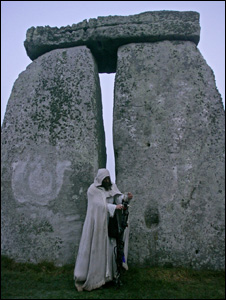

The Altar Stone lies at 80° to the main solstitial axis beneath the collapsed upright of the Great Trilithon (Stone 55b) and its lintel (Stone 156), sunk into the grass. The stone itself was broken by the fall of the Great Trilithon’s upright and is in two pieces. IMAGE SOURCE

New research, led by Aberystwyth University, analysed 58 rock samples from all over the country to figure out where the curious Bronze Age rock may have come from.

For the last 100 years the Stonehenge Altar Stone has been considered to have been derived from the Old Red Sandstone (ORS) sequences of south Wales, in the Anglo-Welsh Basin, although no specific source location has been identified,’ the scientists say.

‘We have concluded that the Altar Stone appears not, in fact, to come from the ORS of the Anglo-Welsh Basin and further, we propose that the Altar Stone should no longer be included in the “bluestone” grouping of rocks essentially sourced from the Mynydd Preseli.

‘Attention will now turn to the ORS of the Midland Valley and Orcadian Basins in Scotland as well as Permian-Triassic of northern England to ascertain whether any of these sandstones have a mineralogy and geochemistry which match the Stonehenge Altar Stone.’

Stonehenge’s most prominent slabs – the sandstone sarsens – were sourced locally, from Marlborough Downs, a mere 20 miles from the monument’s site.

But the origin of the Altar Stone – which lies partially hidden under two fallen columns – has been at the centre of mystery for centuries.

Previous investigations suggest its geology completely contrasts to the rocks found in Wiltshire, and may have been sourced from a quarry 140 miles away.

This Welsh site is home to various other ‘bluestones’ like the Altar Stone, formed when lava cools before crystallising and solidifying.

But new research suggests the so-called ‘Stone 80’ should be ‘de-classified’ as a bluestone due to its unique characteristics.

After conducting 106 analyses, experts say the Altar Stone has an unusually high content of Barium.

This matched just one sample taken from rocks across south Wales, the Welsh Borders, the West Midlands and Somerset.

Now, the team have expanded their search for the source to northern Britain, in the hopes of finding similar geology in Caithness and even Orkney, Scotland.

If it were sourced in Orkney, ancient builders may have dragged the six-ton rock across roughly 682 miles.

This took place thousands of years before heavy-lifting machinery was even invented.

‘Monoliths used in the construction of stone circles are usually locally derived,’ scientists added.

‘It is the long-distance transport of the bluestones that makes Stonehenge of particular interest.

The bluestones in fact represent one of the longest transport distances known from source to monument construction site anywhere in the world.’

Some experts theorise that the Altar Stone was shipped on a raft up the Bristol Channel, before travelling the final leg to Salisbury Plain over land.

However, more recent studies have called this into question and suggest the rock may have been hauled across numerous hills.

The truth of this remains unknown, but MailOnline has approached the experts of this study to hear their thoughts.

RELEVANT STONEHENGE LINKS:

The Stonehenge Altar Stone was probably not sourced from the Old Red Sandstone of the Anglo-Welsh Basin: Science Direct

The Altar Stone – Not welsh, so where is it from? The Sarsen

Stonehenge’s Altar Stone did NOT come from Wales: The Daily Mail

The Stones of Stonehenge On this site you’ll find photos of every stone at Stonehenge/ Simon Banton

Visit Stonehenge with the experts and hear all the latest discoveries and theories – STONEHENGE GUIDED TOURS

Private Guided Tours of Stonehenge with local expert tour guides – STONEHENGE AND SALISBURY GUIDED TOURS

The Stonehenge News Blog

Follow us on Twitter and Facebook for all the latest Stonehenge News

http://www.Stonehenge.News

carved initials and names on the stones. One of them might even be that of Christopher Wren – a local lad who made good and went on to design the new St. Paul’s Cathedral after the Great Fire of London in 1666.

carved initials and names on the stones. One of them might even be that of Christopher Wren – a local lad who made good and went on to design the new St. Paul’s Cathedral after the Great Fire of London in 1666.