New experiment suggests monumental stones could have rolled on rails.

It’s one of Stonehenge‘s greatest mysteries: How did Stone Age Britons move 45-ton slabs across dozens of miles to create the 4,500-year-old stone circle?

U.K. archaeology students attempt to prove a rail-and-ball system could have moved Stonehenge stones

Now a new theory says that, while the ancient builders didn’t have wheels, they may well have had balls. (See Stonehenge pictures.)

A previous theory suggested that the builders used wooden rollers—carved tree trunks laid side by side on a constructed hard surface. Another imagined huge wooden sleds atop greased wooden rails.

But critics say the rollers’ hard pathway would have left telltale gouges in the landscape, which have never been found. And the sled system, while plausible, would have required huge amounts of manpower—hundreds of men at a time to move one of the largest Stonehenge stones, according to a 1997 study.

Andrew Young, though, says Stonehenge’s slabs, may have been rolled over a series of balls lined up in grooved rails, according to a November 30 statement from Exeter University in the U.K., where Young is a doctoral student in biosciences.

Young first came up with the ball bearings idea when he noticed that carved stone balls were often found near Neolithic stone circles in Aberdeenshire, Scotland (map).

“I measured and weighed a number of these stone balls and realized that they are all precisely the same size—around 70 millimeters [3 inches] in diameter—which made me think they must have been made to be used in unison, rather than alone,” he told National Geographic News.

The balls, Young admitted, have been found near stone circles only in Aberdeenshire and the Orkney Islands (map)—not on Stonehenge’s Salisbury Plain.

But, he speculated, at southern sites, including Stonehenge (map), builders may have preferred wooden balls, which would have rotted away long ago. For one thing, wooden balls are much faster to carve. For another, they’re much lighter to transport.

Proof of Concept

To test his theory, Young first made a small-scale model of the ball-and-rail setup.

“I discovered I could push over a hundred kilograms [220 pounds] of concrete using just one finger,” he said.

With the help of his supervisor, Bruce Bradley, and partial funding from the PBS series Nova, Young recently scaled up his experiment to see if the ball-and-track system could be used to move a Stonehenge-weight stone.

Sure enough, they found that, with just seven people pushing, they could easily move a four-ton load—about as heavy as Stonehenge’s smaller stones.

Using the ball system, Young said, “I estimate it would be possible to cover 20 miles [32 kilometers] in a day” by leapfrogging track segments.

But the inner circle’s “sarsen” stones weigh not 4 tons but up to about 45 tons. Young suspects a Stone Age system could have handled much heavier loads than his experimental one.

For one thing, he thinks oxen, not people, provided the pulling power—an idea supported by the remains of burned ox bones found in ditches around many stone circles.

For another, Britain’s old-growth forests hadn’t yet been razed 4,500 years ago, so the builders would have had easy access to cured oak. This tough wood—which was beyond the modern project’s budget—would have resulted in a stronger, more resilient system than the soft, “greenwood” system the researchers built.

Stonehenge Experiment Needs Scaling Up

Civil engineer Mark Whitby, who’s been involved with other Stonehenge-construction experiments, thinks the ball method could work for smaller stones but isn’t convinced it could shift a sarsen.

“The problem will be when the tip of the ball bears on the timber trough, it will bite” into the trough, possibly splitting the rail, said Whitby, who runs London-based +Whitby Structural Engineers. “When transporting lighter stones, this won’t be a problem. But when they get to 30 and 40 tons, it will be.”

Instead, Whitby prefers the sled theory—and even helped prove a sled could move a 40-ton replica sarsen for a 1997 BBC documentary.

Archaeologist David Batchelor, meanwhile, thinks the ball idea is plausible but isn’t completely convinced.

The ball technique “seems to be a development of the sledge method,” said Batchelor, of the government agency English Heritage. “But the added complexity needed to channel the track runners and then make the ball bearings all of one size seems to me a lot of work, which is probably unnecessary when animal-fat grease does the job.”

Research leader Young counters that the sled system, even with its animal-fat lubrication, still results in a lot of friction.

“Using wooden balls almost removes friction from the system and makes for a really efficient method of moving heavy weights around,” he said.

Even so, Young realizes he needs to prove the new system can be scaled up to handle heavier loads. To that end, Young’s team is seeking funding to repeat the experiment—this time with harder wood, stone balls, and oxen

What a load of old balls……………………………..

Merlin @ Stonehenge

The Stonehenge Stone Circle Website

Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology in Austria discovered a major ceremonial monument less than one kilometre away from the iconic Stonehenge.

Ludwig Boltzmann Institute for Archaeological Prospection and Virtual Archaeology in Austria discovered a major ceremonial monument less than one kilometre away from the iconic Stonehenge.

Mapped: The site, ringed, in a Seventies chart, which experts say shows a fence

Mapped: The site, ringed, in a Seventies chart, which experts say shows a fence ‘Evidence’: The radar image said to reveal the post holes of a Neolithic temple

‘Evidence’: The radar image said to reveal the post holes of a Neolithic temple Circle of confusion: An artist’s impression of how Woodhenge may have been 5,000 years ago

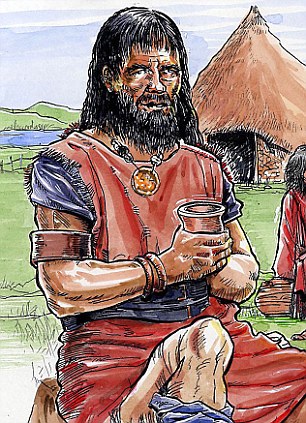

Circle of confusion: An artist’s impression of how Woodhenge may have been 5,000 years ago How a Neolithic visitor may have looked

How a Neolithic visitor may have looked